Abstract art stops people in their tracks. Sometimes in wonder. Sometimes in total confusion.

Unlike realistic art that shows things we recognize, abstract art goes beyond what we see in the visual reality around us. The abstract art meaning isn’t about accurate depiction—it focuses on feelings, movement, colors, and shapes rather than telling a clear story.

That doesn’t stop most people from asking themselves “What the heck am I even looking at?”

Here’s the good news: Understanding abstract art doesn’t require a deep understanding of the art world. You just need to be open to finding your own meaning instead of looking for what something is supposed to represent.

Let’s explore why non-representational art matters, how abstract artists create work that moves us (even when it seems weird), and how to understand art that breaks traditional rules.

Quick Tips for Understanding Abstract Art

- Trust your first reaction—understanding abstraction starts with what you feel, not what you “should” see

- Look at colors in abstract painting—do they make you feel calm, excited, or something else?

- Notice the art form itself—are shapes and lines soft and flowing or sharp with gestural marks?

- Step back to see the whole picture, then move closer to spot details

- Abstract art requires no single “correct” view—your own meaning is just as valid as anyone else’s

- Remember that modern art, including abstract expressionism, invites personal interpretation

Share these with a friend who gets nervous in art museums!

Where Did Abstract Art Come From?

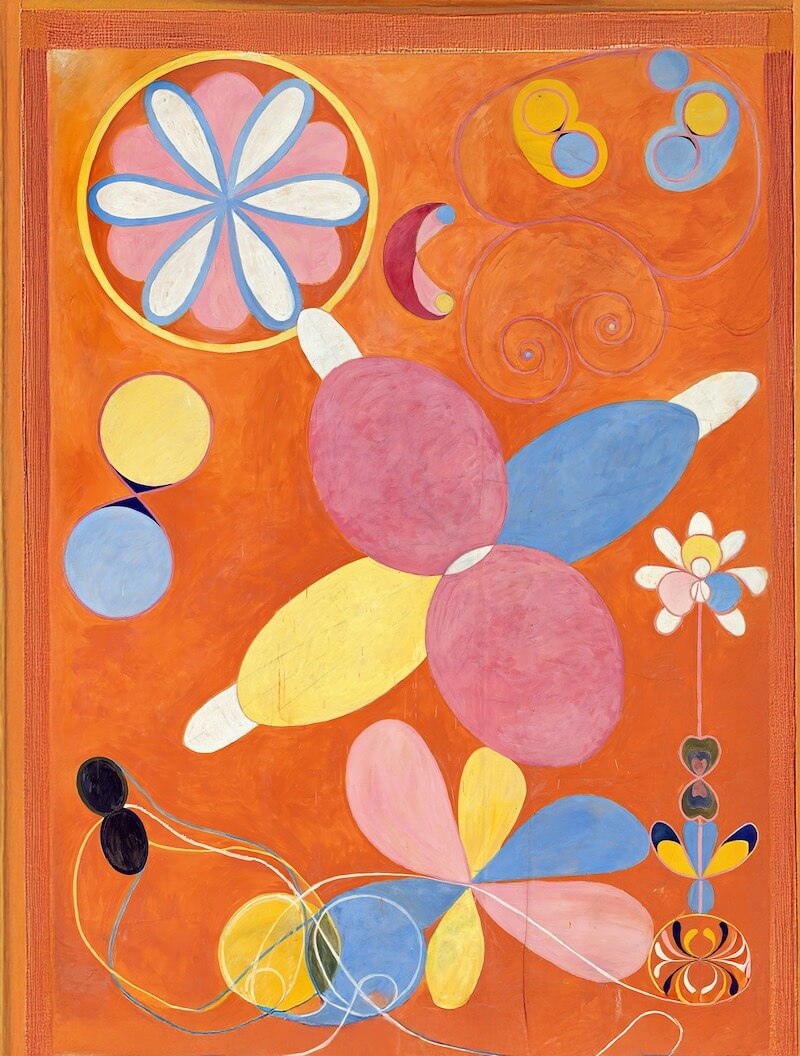

Hilma af Klint’s The Ten Largest, No. 4 (1907)

Abstract art didn’t just appear out of nowhere.

For hundreds of years, art was supposed to represent reality—people, places, landscapes, religious scenes. Botanical artists even staked their livelihood on how accurately they could represent reality. But as the world changed, so did the art world.

Why Art Moved Away From Representational Art

When cameras came along in the late 1800s, artists no longer needed to create art that showed accurate depiction of scenes. Photos could do that job better and faster.

This freed artists to try new things that went beyond visual reality.

Science was changing too. Einstein’s ideas and new physics made people question how we see the world. Nietzsche and Bergson invited debate on experience vs. truth. In response, abstract artists began to paint feelings and ideas instead of just things.

African art, with its bold stylization and symbols, inspired European artists to break their old rules about what art requires to be considered “good.” You can see this inspiration in painters like Picasso and Matisse.

Some modern art pioneers, like Kandinsky, Malevich, and Mondrian, felt art should express spiritual ideas through pure abstraction and pure art forms—not just copy what the eye can see.

The Path to Abstract Art

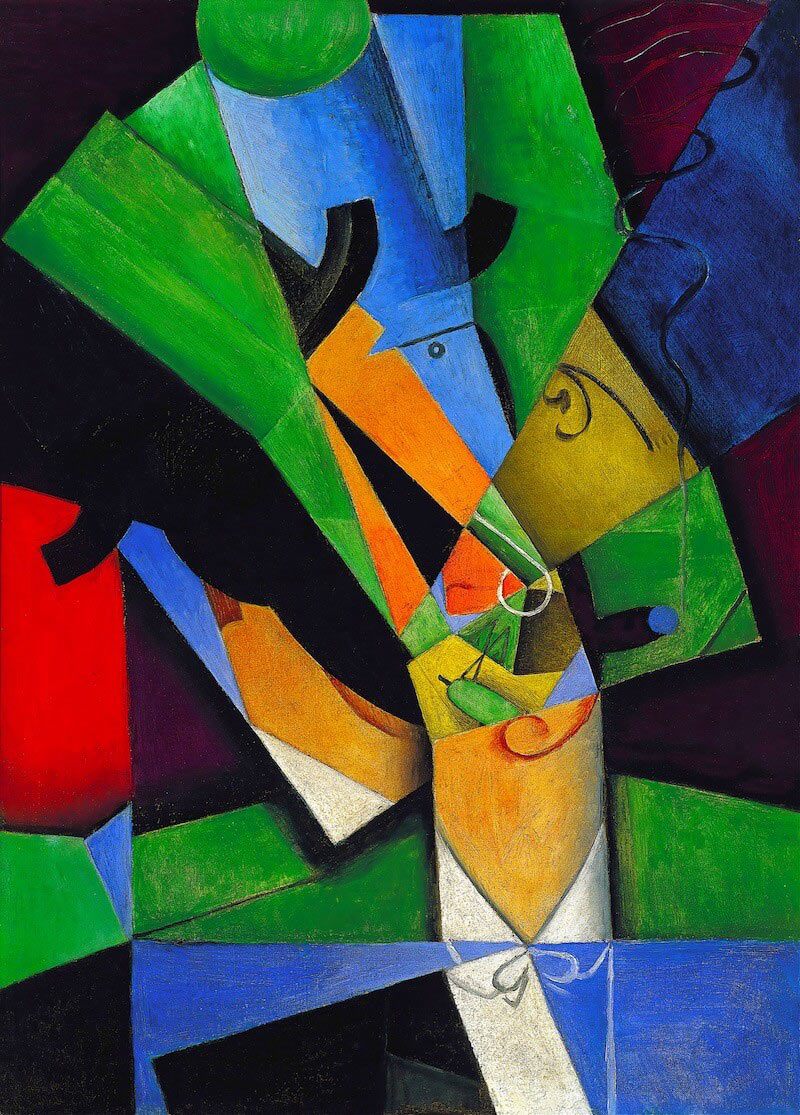

Juan Gris’ The Smoker (Frank Haviland) (1913)

Modern art grew step by step, moving further and further away from realistic art:

Impressionism (1870s–1890s): Monet and Renoir used loose brushstrokes that began to break from strict realism.

Post-Impressionism (1880s–1900s): Van Gogh and Cézanne cared more about feeling and art form than perfect copies of visual reality.

Fauvism (1905–1910): Matisse and Derain used wild, unnatural colors to express emotions rather than represent reality.

Cubism (1907–1914): Picasso and Braque broke objects into geometric shapes, a step toward non-representational art.

Each movement took the art world further from showing things exactly as they appear, paving the way for pure abstraction.

Big Names and Movements in Abstract Art

Let’s look at the most important abstract art styles and the abstract artists who created them.

Suprematism & Constructivism: Pure Shapes

Kazimir Malevich’s House Under Construction (1915)

Russian artists took abstraction to the extreme by creating pure art using only the most basic shapes. Suprematists sought “zero degree” art—the point beyond which art ceased to be art.

Kazimir Malevich painted Black Square (1915)—just a black square on white. It was art stripped down to nothing but form, a perfect example of pure abstraction.

El Lissitzky created works like Proun Room (1923) with simple shapes to show movement and structure through space.

These artists believed art didn’t need to show anything real—the art form could just be shapes, colors, and spaces. Their work required viewers to understand art differently.

De Stijl: Finding Order

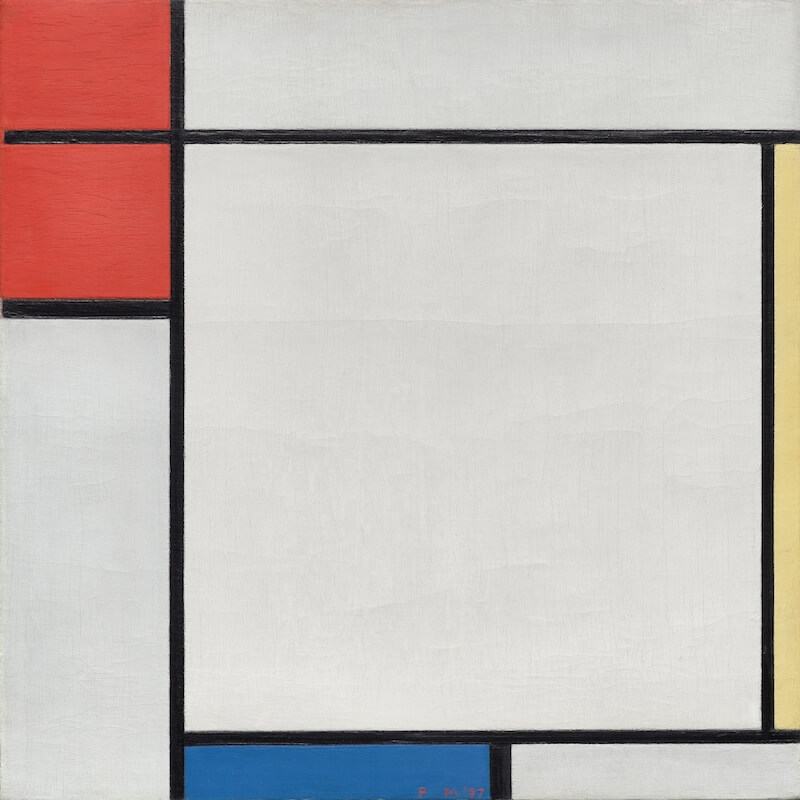

Piet Mondrian’s Composition with Red, Yellow, and Blue (1927)

After the chaos of World War I, Dutch artists tried to create order through simple geometry.

Piet Mondrian made famous grid paintings using only primary colors (red, blue, yellow) with black lines. He wanted to find perfect balance. Mathematics became harmony.

Theo van Doesburg added diagonal lines to make these ideas more dynamic. He developed Elementarism, which added dynamism to De Stijl (“The Style”).

These artists tried to find the most basic visual building blocks—like finding the DNA of art.

Abstract Expressionism: Raw Emotion

After World War II, American artists flipped the script. They focused on raw feelings and spontaneous action over geometric precision.

Jackson Pollock created his famous drip paintings by splattering paint across huge canvases, making the act of painting itself the point. Many abstract expressionists came to be called “action painters” for how their wild movements and emotional experience while painting enriched the artwork.

Rothko did something different. He painted huge blocks of color that feel calm, almost spiritual. Totally different from the wild energy of other abstract expressionists.

Other artists used forms and gestural marks in their abstract work.

Abstract expressionism cares more about real feelings than pretty pictures. Raw emotion over perfect copies of things.

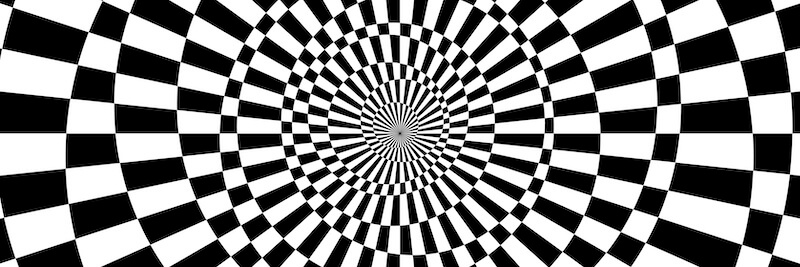

Op Art: Tricking Your Eyes

Some artists in the 1960s played mind games with paint.

Victor Vasarely, the “grandfather of Op Art,” made patterns that seem to pulse and move right in front of you. Take a look at Vega III (1957)—your brain won’t believe you that it’s flat.

Bridget Riley? Black and white lines that make your eyes go crazy. Look too long at Movement in Squares (1961) and you might get dizzy.

Capitalizing on new scientific discoveries about vision and perception, these artists showed how our eyes and brain can be fooled. Pretty clever stuff.

Minimalism: Less is More

Then came the minimalists. Strip it all away into total abstraction.

Frank Stella used clean, simple lines. No hidden meanings or deep stories—just what you see.

Josef Albers got obsessed with squares. Put different colors next to each other and watch how they change. Expression through science and color psychology.

Abstract art isn’t just one thing. Wild emotional splashes. Clean perfect grids. Eye tricks. It’s all about breaking free from copying what we see. What connects them all is moving beyond copying reality to explore color, shape, and feeling.

What Makes Art Abstract?

Understanding abstract art requires knowing its key features that set it apart from traditional, realistic art:

- Focus on the art form itself: Color, shape, line, and texture matter more than accurate depiction of objects.

- Open to interpretation: There’s no single “right” way to understand abstract art. Your own meaning is valid. Engage with modern wall art on a personal level.

- Expression over representation: Abstract artists show feelings and ideas rather than trying to represent reality.

- Range of styles: Some abstract painting contains hints of real things. Other works use pure shapes and colors with no reference to visual reality—this is non-representational art. Gestural marks often borrow elements of Surrealism, focusing on subconscious design.

- Different measures of success: Good abstract art isn’t about looking “real”—it’s about creating balance, energy, or feeling through basic elements.

Your understanding of abstraction will differ from others because we all bring different life experiences to what we see. And that’s okay. That’s exactly what makes modern art special.

Without representing reality in obvious ways, abstract art requires you to explore your own feelings to create your own meaning.

How to Look at Abstract Art

Understanding abstract art isn’t about finding the “correct” meaning. It’s about having your own experience with the abstract painting.

Instead of asking “What is this supposed to be?”, try asking:

- How does this artwork make me feel?

- Do the colors seem happy, sad, calm, or angry?

- Do the shapes and gestural marks feel stable or chaotic?

- How are the colors and forms interacting?

- Does the artwork help me see visual reality differently?

- What personal meaning can I find in this piece?

Abstract art thrives on being personal. What you think about the art matters just as much as what the artist meant. Maybe more.

You might love Pollock’s energetic splatters. Or find peace in Mondrian’s tidy grids. Or get mesmerized by Riley’s eye-bending patterns.

The secret?

Drop your expectations.

Stop looking for the “right” answer.

Just see what happens inside you when you look.

That’s the whole point of abstract art. It wants you to find your own beauty in shapes and colors that don’t try to be something else. So next time you see abstract art and think “How is this even art?”, take a breath. Let the artwork speak to you in its own language.

Because in abstract expressionism and other abstract styles, the meaning comes from your personal connection with it.