Often considered the “father of Impressionism,” Claude Monet is one of the most important artists of the late 19th century. While it’s not the most famous Claude Monet painting, Impression, Sunrise (1872), helped coin the term “Impressionism” and paved the way for a veritable revolution in the world of fine art.

As a pioneer of a whole new style, Monet was controversial among critics at the time. His career went from critical and academic dismissal to widespread acceptance and acclaim. His ideas signaled a massive change in the avant-garde and even today, his work continues to artists and museums all over the world.

Modern art as we know it can be effectively divided into a pre- and post-Monet timeline. Discover who Monet truly was and why his art stands the test of time.

10 Interesting Facts About Claude Monet

- Claude Monet’s birth name was Oscar-Claude Monet, but he dropped the “Oscar” early in his life.

- His painting Impression, Sunrise gave the entire Impressionist movement its name—though it was initially used by a critic as an insult!

- Monet’s famous water lily garden in Giverny wasn’t natural. Monet diverted a river and designed the entire garden himself. Who knew his artistic talents included landscaping?

- Claude Monet painted about 250 water lily paintings over the last 30 years of his life, becoming almost obsessed with capturing the changing light on his pond.

- Later in life, he suffered from cataracts, which affected his ability to see colors. Paintings from this period show a distinct reddish tone because that’s how he perceived the world.

- After cataract surgery, Monet actually destroyed some of his earlier works because he could finally see how “wrong” the colors were.

- Despite being known for outdoor “plein air” painting, Monet often worked on his large canvases in his studio, using smaller outdoor sketches as references.

- Monet was quite poor for much of his early career. His friend and fellow painter Édouard Manet once secretly bought one of Monet’s paintings at an auction to help him financially.

- He was incredibly dedicated to capturing the perfect light. Sometimes, he worked on multiple canvases at once, switching between them as the light changed throughout the day.

- Monet’s home in Giverny featured vibrant yellow dining room walls and brilliant blue kitchen tiles—his love of bold colors extended beyond his canvas to his living space.

From Paris Boy to Budding Artist

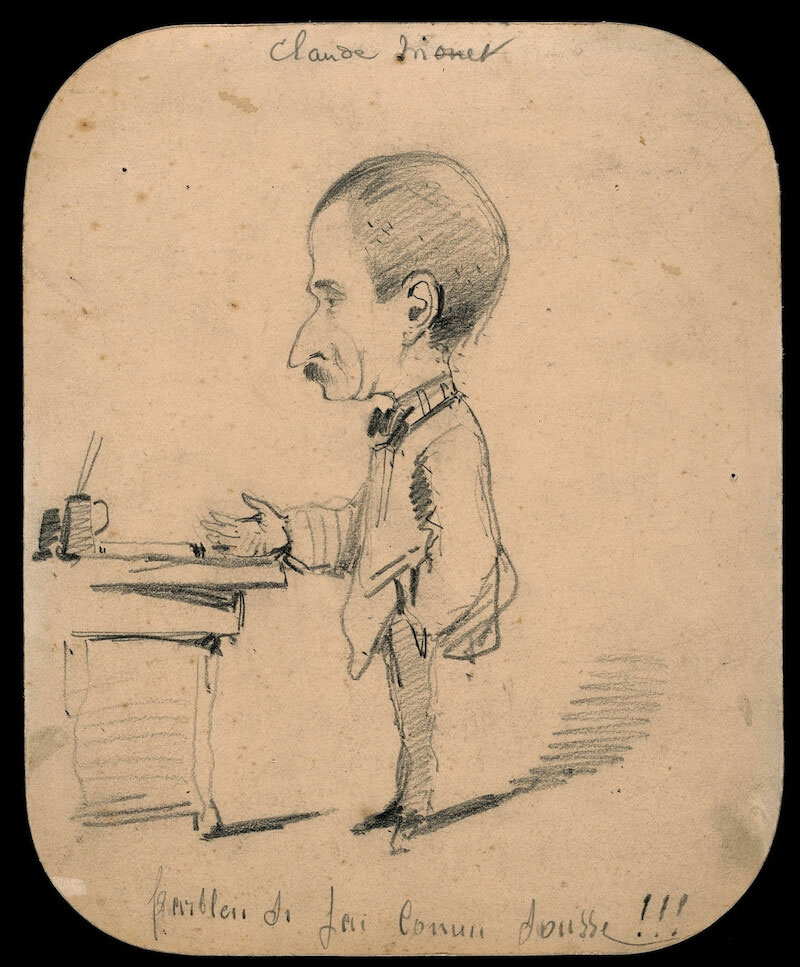

Monet’s Caricature of a Man Standing by Desk (1855)

Oscar-Claude Monet was born on November 14, 1840, in Paris, France. He was the second son of Claude-Adolphe and Louise-Justine Aubrée Mone. When he was five, his family moved to Le Havre in the Normandy region of France.

From childhood, Monet took an interest in art. His mother, who was an artist in her own right, encouraged him, even though Monet’s father, a grocer, would have preferred his son to take up his own profession. By the age of 11, Monet had already started taking drawing lessons from Jacques-François Ochard, a former student of the highly regarded Neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David.

Even at this early age, Monet was known to draw caricatures of teachers and classmates, which he would then sell for 10–20 francs. This foreshadowed the independent spirit that would define his later career.

Meeting His Mentor and Finding His Path

Monet’s The Beach at Honfleur (1864-1866)

In 1858, while walking along a beach in Normandy, an 18-year-old Monet came across Eugène Boudin. This chance encounter would prove fateful for the young Monet. Quickly recognizing Monet’s talent, Boudin encouraged him to begin painting landscapes rather than caricatures.

What was novel about Boudin’s approach was his insistence on painting en plein air: that is, working outdoors instead of in a studio. This later became a major characteristic of the Impressionist movement.

It wasn’t long before painting sessions with Boudin brought Monet to “see the light” in the fullest sense. He would remark about these formative years: “Boudin taught me to observe. He opened my eyes.”

The time the two spent painting together set the foundations for Monet’s famous landscape paintings and his signature foregrounding of natural light and color.

The Birth of Impressionism

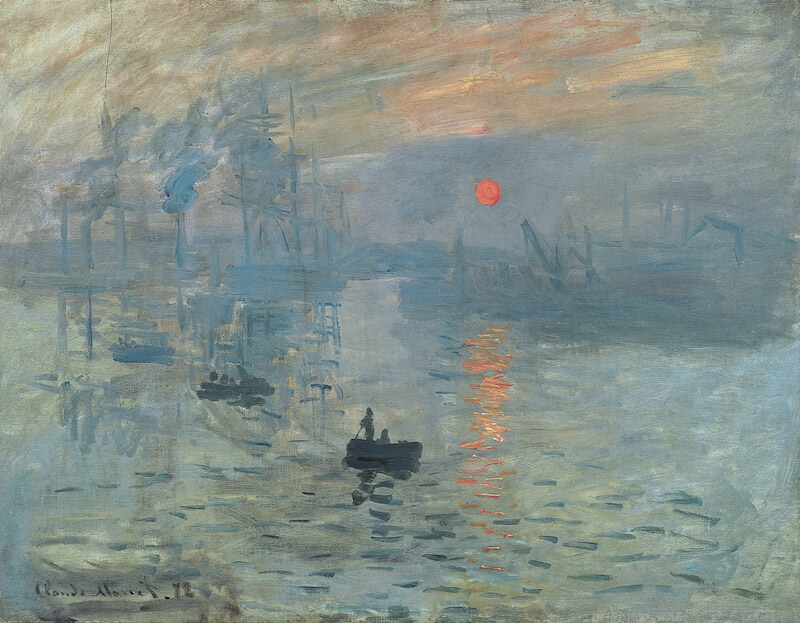

The town of Le Havre provided the theme for Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872). This painting—debuted in 1874 at an exhibition organized by Monet and his colleagues—depicts a seaside vista in Le Havre shrouded in cold blue hues while the rising sun introduces a warm orange palette. While the colors contrast with the darker vessels stippling the canvas, representational detail is kept to a minimum.

Impression, Sunrise is strongly atmospheric in its depiction of natural light. The Impressionist aesthetic of visible brushwork, the prioritizing of light and color, and the recreation of a momentary “impression” rather than a staunch, realistic representation, is already apparent in this early work.

When Impression, Sunrise was first exhibited, one critic, Louis Leroy, seized on the title and used it to deride what he felt was an overall unfinished, sketchy painting. An “impression” of a painting rather than a finished work. This backfired, however, when Monet and his colleagues came to welcome the label.

Family Life: Joy and Heartbreak

Monet’s Camille on the Beach in Trouville (1870)

Monet first met Camille Doncieux in 1865 when she modeled for one of his paintings. The two soon became involved, and in 1868 Camille Monet gave birth to their first son, Jean. On June 28th, 1870, the couple were married.

Camille gave birth to their second son, Michel, in 1878. But she succumbed to tuberculosis shortly thereafter, when she was only 32. In her final days, Monet painted one last portrait of his bedridden wife, which can be viewed today at the Musée d’Orsay.

Amidst all this turmoil, Alice Hoschedé had entered the picture. Alice was married to Ernest Hoschedé, an early patron of Impressionism, whose financial situation had recently fallen into ruins. The Hoschedé family moved in with the Monets to save money. When Ernest Hoschedé died, Alice agreed to marry Monet in 1892.

The blending of two families laid the groundwork for a relationship that would profoundly affect Monet. Alice offered him the emotional support he needed to continue his artistic pursuits and ensured that their children grew up in a nurturing environment.

Creating Giverny: Monet’s Living Canvas

Monet’s The Japanese Footbridge and the Water Lily Pool, Giverny (1899)

Monet discovered the village of Giverny in 1883. Searching out an affordable place to live for his now sizable family, a particular house around 50 miles northwest of Paris caught his attention. He was captivated not only by its stature but also by its lush surrounding orchards and its quite beautiful gardens.

For Monet, Giverny quickly became an obsession. He diverted the river flowing through the property to enlarge its pond, filling it with exotic flowers. He also installed the Japanese-inspired bridge which features in many of his paintings.

A quote attributed to Monet goes: “My garden is my most beautiful masterpiece.” Planting orange, pink, gold, and bronze wallflowers and tulips by the thousands, his garden became a personal laboratory for his work. Its many color schemes provided plenty of subject matter for some of his most celebrated paintings.

Painting in Series: Capturing Time and Light

By the 1890s, Monet pioneered a method of producing repeated studies of the same motif in series, working on different canvases in accordance with changes in light and season. These series were intended to be exhibited in groups—for example, his Haystack paintings (1890–1891), and his later paintings of the Rouen Cathedral (1892–1894). This new way of painting focused on carefully watching a scene for a long time and showcasing the changes.

Perhaps most famously, this serial method culminated in Monet’s last series of works: Water Lilies (1897–1926).

Monet’s serial approach to painting, which emphasized light and color over any particular subject, laid the groundwork for art movements that emerged well into the 20th century—not only the early post-Impressionists, who emerged during Monet’s own lifetime, but also what would later become Abstract Expressionism.

Monet’s Famous Paintings

Impression, Sunrise (1872)

Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872)

Impression, Sunrise (1872) signaled the emergence of Impressionism. This modestly sized work (18 x 24 inches) had a massive impact: it scandalized critics and the general art-going public when it was first exhibited in 1874.

The painting appears to capture a quiet early morning at Le Havre’s port, but closer inspection reveals nascent tendencies of a budding avant-garde movement. Long before people were decorating their homes with abstract art, this departure from literalism was hard to understand.

Monet painted mist as gauzy curtains throughout the whole scene. The blue-grey water contrasts the pervasive orange of the sun and plays again the dark silhouettes of small boats. Louis Leroy, the infamous critic who derided the painting when it first debuted, actually said: “Impression—I was certain of it. I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it… and what freedom, what ease of workmanship! Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape.”

“Impressionism” became the watchword for a new way of perceiving and relating to painting. The label launched a revolutionary new attitude in the realm of fine art. Today, the painting that changed the course of art history can be viewed at the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris.

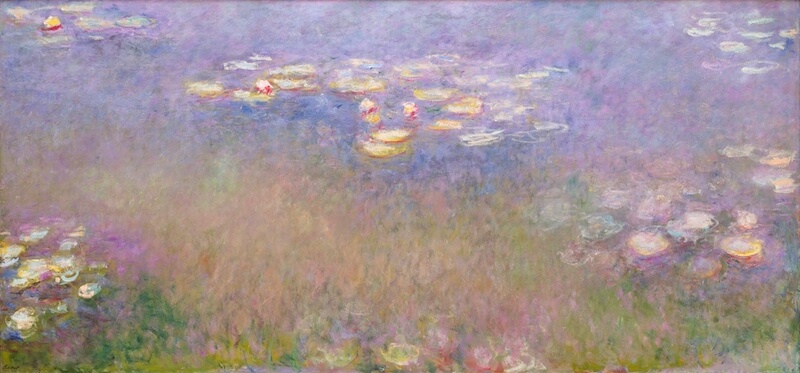

Water Lilies Series (1897–1926)

Monet’s Le Bassin des Nympheas (1904)

Painted from 1897 until Monet’s death in 1926, Monet’s Water Lilies, or Nymphéas, series includes around 250 works. In a letter, Monet wrote how “these water landscapes have become an obsession. They’re beyond the strength of an old man, but I want to succeed in rendering what I feel.”

Monet had planted water lilies around his pond in Giverny. They flourished among the weeping willows, exotic flowers, bamboo trees, and the small Japanese bridge he installed. True to fashion, his paintings reflected his impression of the scene rather than the scientifically accurate details one would find in botanical art.

Eventually, Monet’s Water Lillies led to what he called the Grandes Décoration. These mural-sized paintings blur the boundaries between land and water, garden, and pond. They even hint at the modern dichotomy of figuration and abstraction.

Today, eight of these massive two-meter-tall panels are displayed in two oval-shaped rooms at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris. Together, they’re nearly 328 feet long. It’s a true magnum opus for his decades-long series.

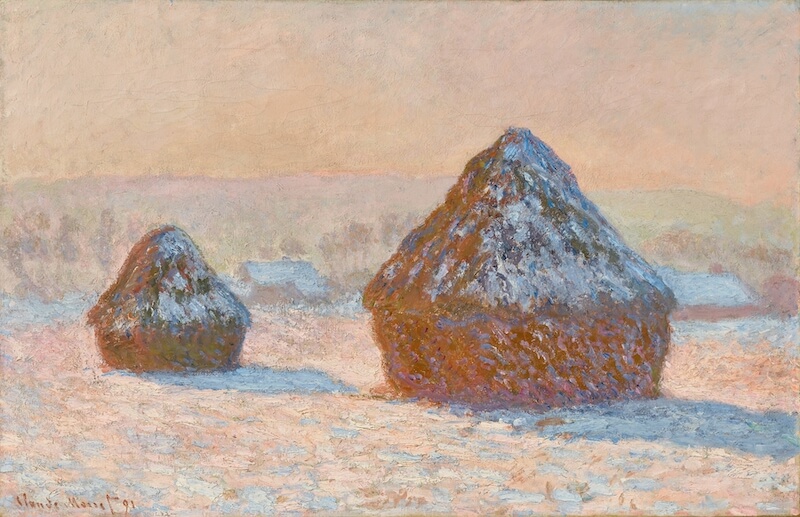

Haystacks Series (1890–1891)

Monet’s Wheatstacks, Snow Effect, Morning (1891)

Monet began painting his Haystacks series in late summer in 1890 and kept working on it through the next spring. This series of 25 paintings uses repetition to showcase how light changes during different times of day, seasons, and weather. Every painting is of the same haystacks—yet they all look different. The haystacks themselves were located near Monet’s residence in Giverny.

Monet’s chose a humble, ordinary subject because the subject wasn’t the point. He was focused on how light and atmosphere could change how anything looked. His haystacks aren’t meant to be paintings about farm objects—they’re a thesis on how paintings can preserve the momentary, transformative effects of time, light, and color.

The series became very famous, and one of these Les Meules paintings (French for “the stacks”) sold at Sotheby’s for a record-breaking price in 2019, underscoring how important they still are in the world of art today.

Rouen Cathedral Series (1892–1894)

Monet’s Rouen Cathedral, West Façade, Sunlight (1894)

In 1892, Monet rented rooms across from the Rouen Cathedral in Normandy. From there, he painted the front of the cathedral over and over, using thick, textured brushstrokes to show how light and air changed the way it looked.

Between 1892 and 1893 he painted the cathedral more than 30 times, each painting showing how different times of day—from foggy mornings to bright afternoons to glowing sunsets—transformed the building’s stone surface.

This series marked a big shift in Monet’s work. Instead of focusing on the details of the carved Gothic façade, he began focusing more on the light and atmosphere around it. The paintings almost look abstract, as if the brushstrokes themselves are the main subject. By following his instincts instead of sticking to a strict plan, Monet helped pave the way for later artists, like those in the Abstract Expressionist movement.

The Houses of Parliament, Sunset (1903)

Monet’s The Houses of Parliament, Sunset (1903)

Monet painted the Houses of Parliament during several trips to London from 1899 to 1901, working from a terrace at the nearby St Thomas’ Hospital. He went there at the same time each day in the late afternoon, so it’s not the time that’s changing—it’s the weather. Monet was fascinated by the London fog.

These paintings are characterized by their soft, blurred edges and muted colors, which create a dreamlike quality. The subtlety of the atmospheric effects established a new direction in Monet’s work, which leaned ever more toward abstraction.

The series includes 19 works, part of a larger collection of more than 100 paintings of the Thames River. His interest in London’s fog and how it filtered the light of the River Thames remains one of the most celebrated offshoots of his serial way of working.

Final Years and Legacy

Monet’s Water Lilies (c. 1915–1926)

Monet developed cataracts in his 60s. When they grew quite advanced and he could no longer depend on the accuracy of his eyesight, he placed labels on his paint bottles and selected what he needed based on the label, rather than color.

Despite this, Monet continued to develop his large-scale Water Lilies—the size of which might have compensated for his increasingly poor eyesight. These paintings—about six and a half feet high, and 42 feet wide—were worked and reworked over many years. In the midst of this series, however, Monet’s health started to decline. He died of lung cancer on December 5, 1926, at the age of 86, and was buried in the Giverny church cemetery.

Perhaps due to his failing eyesight, Monet’s final paintings increasingly resembled abstract art. These innovations, however, laid the groundwork for later art movements such as Post-Impressionism (Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat), Fauvism, and Abstract Expressionism. Today, Monet’s Giverny home and its spectacular garden—beautifully restored—still draw artists, art lovers and tourists alike. And his paintings, particularly from his Haystacks series, continue to break auction records.

Why Monet Still Matters Today

Monet created a special style of painting that showed how people experience nature in the moment. Instead of painting narratives or trying to paint things exactly how they looked, he used color and careful brushwork to paint moods and feelings.

Monet’s work is exhibited worldwide at the Musée Marmottan Monet (Paris), The Metropolitan Museum of Art (NY), Kunsthalle Hamburg (Germany), the Fondation Beyeler (Switzerland), and the São Paulo Museum of Art (Brazil), among others. His water garden at Giverny, which he designed with the same meticulous attention he gave to his paintings, remains a living conduit for his deepest source of inspiration.

Monet once remarked: “Everyone discusses my art and pretends to understand, as if it were necessary to understand, when it is simply necessary to love.” It’s this feeling that magnifies Monet’s vision. He articulated the world through light and color, transcending the need for arguments and analysis.