If you love bold, vivacious colors, you’ll swoon over Fauvism.

Fauvism was an early 20th-century art movement spearheaded by a group of artists nicknamed Les Fauves, meaning “the wild beasts” in French.

These freewheeling artists broke away from the conventions of the day. They used bold, non-natural colors and simplified forms to express emotion rather than realistic representation.

The movement was short-lived—barely lasting three years—but its impact was profound. Learn more about the Fauvism movement’s indelible mark on art history and the lasting inspiration it provided to modern and contemporary artists.

The History of Fauvism

Fauvism emerged in France around 1904. The Fauves (or “wild beasts”) were a group of French painters who were inspired by Vincent Van Gogh, Gauguin, Georges Seurat, and Paul Cézanne. Together, they stoked the embers of their shared interest in pushing color to its sublime extremes.

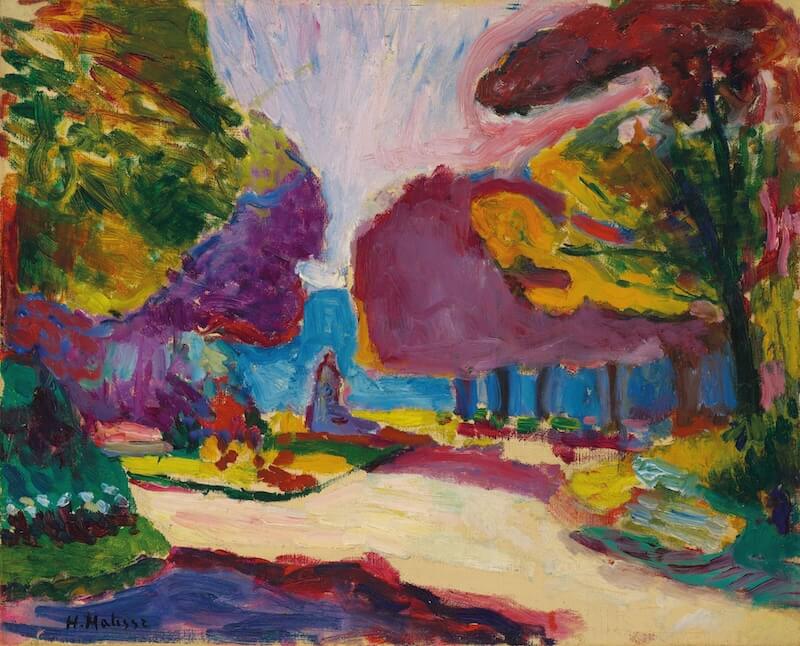

Several of Fauvism’s key figures—including Henri Matisse, Albert Marquet, and Georges Rouault—were students of the Symbolist artist Gustave Moreau. Moreau taught them the power of personal expression in art, shaping Fauvism’s use of intense, non-naturalistic colors and its non-literal portrayal of reality.

The Fauves were testing their own boundaries, but they never set out to be wild beasts.

The nickname came from the controversial Salon d’Automne exhibition in Paris (1905)—featuring works by André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, and Henri Matisse (among others). Art critic Louis Vauxcelles published a scathing review of the show, describing the artists as “Fauves” or “wild beasts.” The label stuck.

The exhibition was a scandalous success. Artists and dealers became instantly drawn to the Fauvist style.

Henri Matisse started selling works to expat writer Gertrude Stein, who introduced Fauvism to an American audience. Ambroise Vollard, an important French dealer, particularly advanced the works of André Derain. The mix of positive and negative attention helped it take off locally and abroad.

Coming together at the height of Europe’s La Belle Epoque, Fauvism hinted at the next chapters of art history. It reflected broader societal shifts in modernity and signaled a general interest in non-Western art forms. Despite the lack of any formal manifesto, Henri Matisse and artists close to his circle shared an interest in color’s expressive capacity and developed this through non-traditional approaches to painting.

By 1907, Fauvism’s influence had spread throughout Europe—particularly in Germany, where it influenced Expressionism. While Fauvism as a style continued beyond 1910, the movement peaked between the years 1905–1908. The three exhibitions that the Fauvists mounted during this time proved to be an invaluable bridge between Post-Impressionism and unknowingly paved the way for contemporary avant garde art.

Key Features of Fauvism

Non-Naturalistic, Vibrant Colors

Matisse’s Seated Riffian (Le Rifain assis) (1912)

Fauvism used wildly contrasting colors in ways that seemed to invite playful exaggerations or to willfully distort the ordinariness of everyday life. The Fauves made color the star of the show, pioneering a new style of painting that foregrounded paint and pigment as a medium all its own.

Sacrificing realistic representation for expressive intensity, Fauvism became one of the earliest art movements to focus on the psychological impact of color. It laid the groundwork for German Expressionism and other avant-garde movements that turned away from naturalistic representation towards more abstract renderings of modern life.

Fauvism proved that the materiality of paint on canvas could evoke intense emotional reactions and carve out new ways of depicting space.

Strong Emphasis on Artistic Freedom

Fauvists turned away from established rules of composition and perspective. They allowed color to exist on the canvas as an independent quality, taking over as the primary aesthetic vehicle.

Colors could project a mood, establishing their own structure within and around a painting’s subject without having to imitate the natural world.

All told Fauvists painted what they felt as much (and even more so) than what they saw. Their inner worlds were transposed into those stylized figures, and their dreamlike color choices were a medium for personal communication.

Out of this new aesthetic turn, each element (gestural brushwork, color saturation, etc,) could serve a higher goal. The immediate visual impression of a painting would be strong and unified by appealing to the artist himself.

Visible, Energetic Brushwork

Matisse’s Jardin du Luxembourg, Paris (1902)

Fauvist painters welcomed paint’s raw, unblended qualities and often laid it thickly onto canvas in an almost textural way (known as “impasto”).

Loose, disjointed brushstrokes lent a certain dynamism to Fauvist compositions—a quality that remains a hallmark of the movement today. Gestural brushwork also emphasized the presence of the artist’s hand, which further enhanced the energy and personality of Fauve paintings.

Flattened Perspective and Space

Inspired by Impressionism, Fauvism abandoned three-dimensional illusionistic space and began to create a new dimension out of color and pigment. Spatial relationships shifted from realistic depictions to symbolic representations.

Impressionist painters like Claude Monet weren’t the only sources of inspiration.

Japanese prints also used ornament and decoration to depict patterns with a personal, symbolic meaning. African influences, likewise, can be sourced from the imagery and inspirations that fed into Fauvism. Using basic mark-making techniques, the goal was to elicit a powerful emotional reaction without having recourse to strict realism.

The Fauvist style embraced simplified forms and unmodulated areas of bright color to showcase decorative, pattern-like qualities that were evocative without being literal. The movement’s synthesis of color, form, and expressivity eliminated the need for optical illusions to create literal depth and scale.

Simplified Forms & Shapes

Albert Marquet’s Paris, Quai du Louvre, Soleil d’hiver (c. 1906)

The Fauves’ bold use of simplified shapes further enhanced the role of bright colors. By stripping away complex forms, pure color took over the rules of realism, like accurate shading, natural lighting, and proper perspective.

Fauvism’s turn away from academic tradition is often considered a triumph of personal expression over technical mastery. Stripping away the representational details of objects and reducing them to simpler, more abstract forms helped bridge the gap between the rigidity of realistic representation and full-on abstraction. Embracing experimentation, Fauvism paved the way for modern art’s evolution.

Key Artists of the Fauvism Movement

Henri Matisse: Pioneer of Fauvism

Matisse’s Nature morte au purro (1904)

One of the most prominent figures to emerge from Fauvism was Henri Matisse.

Matisse’s work is often distinguished by his use of vibrant color and his pioneering use of simplified forms to render figures. Even during his early Fauvist period, he would paint scenes from everyday life, transformed by explosive fields of color.

Henri Matisse relied on a relatively somber palette in his early work. Upon seeing the bright impressionist colors, his work evolved and set the palette that later came to define his output.

His painting style is generally considered representative of the Fauvist movement—especially in the way he merges color and form without regard for exacting detail. Also, typical of Fauvism, he saw color as an independent force that created new potential within the surface of a canvas. Even after Fauvism faded away, Matisse continued his experiments—most notably employing paper and collage in his later works.

Maurice de Vlaminck: Expressive Fauvist

Maurice de Vlaminck’s innovative approach to form and color helped to make him one of the pioneering artists of his day. French-born, his Fauvist paintings are everywhere marked by the expressive and spontaneous brushwork that the movement is known for. Equally, his paintings underscored an emotional and expressive aspect all their own.

Across his chosen subjects, De Vlaminck’s almost Expressionist use of color singled him out as an innovator whose individualistic style would soon take shape as a larger cultural trend. More so than many of his peers, De Vlaminck challenged traditional artistic norms with his intense, non-naturalistic color palette. His depictions of rural French landscapes communicated emotion viscerally, creating space for vivid hues as well as subtle color contrasts.

André Derain: Fauvist Innovator

Derain’s Matisse et Terrus (1905)

The career of French-born André Derain encompassed painting, sculpture, printmaking, and design. He was also among the leading figures of early Fauvism.

Known for his intense use of color, often applied with thick, heavy brush strokes, Derain would allude to a kind of symbolism hidden in abstract artwork. His colorful Fauvist depictions, as well as his later excursions into Cubism, positioned him as one most representative figures in modernist art generally.

Fauvism Compared to Other Modern Movements

Fauvism vs. Expressionism

Derain’s Bords de rivière (c. 1904–1905)

Throughout its brief life, Fauvism was primarily a French phenomenon. Expressionism (not to be confused with Abstract Expressionism), which took a number of cues from Fauvist influences, was initially confined to Germany and Northern Europe in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Expressionism developed around similar ideals as Fauvism, yet focused more on emotional and psychological depth. Whereas Fauvists often painted landscapes, seascapes, cityscapes, and fashionable women in a way recalling the life of a bon vivant, Expressionism explored themes of alienation and anxiety—reflecting the collective European psyche in the midst of the many social tensions that eventually led to WWI.

Ultimately, Expressionism came to signal many diverse approaches not only to art-making but to the themes deemed appropriate for art. Along with this, Expressionism came to incorporate an equally unique array of media: more than just paintings on canvas, Expressionist artists were also known for their works in film and literature. While Fauvism was an inspiration for a number of contemporary artistic disciplines (including print-based media and architecture), Expressionism continued to serve as a catalyst for artistic innovations well into the 20th century.

Fauvism vs. Impressionism

While Impressionism opted for subdued hues and choppy brushstrokes to render minute variations in light, Fauvist artists (heavily influenced by color theory) primarily sought to convey the emotion of the artist’s inner world through nuanced constellations of color and form. This sacrifice of strict realism pushed the Fauvist movement against the limits of Impressionism.

Created by Claude Monet, Impressionism was characterized by an almost documentarian eye for lived experience. Fauvism, on the other hand, sought to create a world apart from what could be seen by the unaided eye—often using realism as a springboard for a unique kind of emotional expressivity.

Impressionism, for all its originality, still had a foot in academic traditions—especially in the methods it used for portraying light. Fauvism, however, constituted a radical departure from these tendencies. Often outlining figures in black contours and substituting non-naturalistic elements for naturalistic ones (yellow sky, for example, or green skin), Fauvism laid the groundwork for numerous currents of abstraction that followed in its wake.

Fauvism vs. Cubism

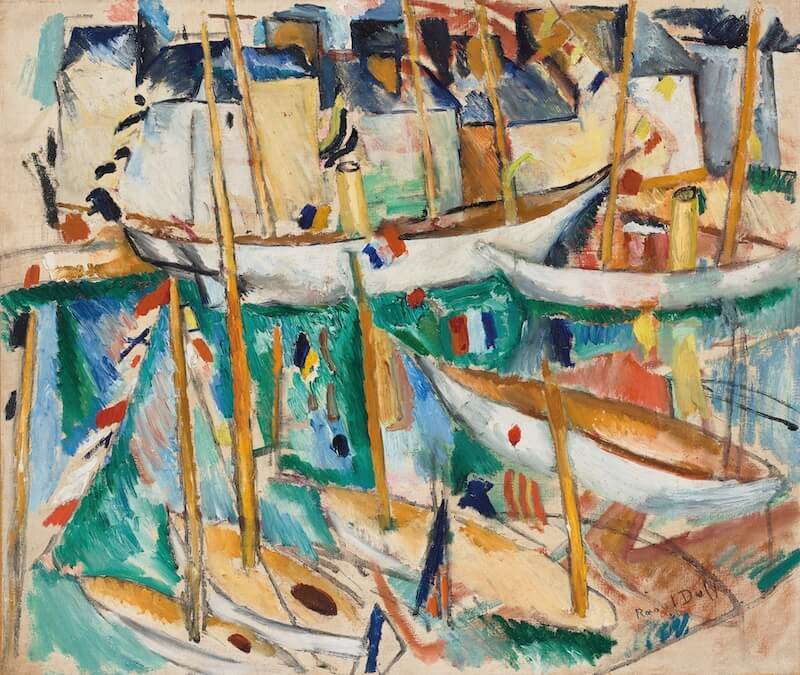

Raoul Dufy’s Les Bateaux (1909–1910)

Fauvism as a movement only lasted for a few years: primarily from 1905–1908. While the three exhibitions that made Fauvism viewable to the public are no match for Cubism’s much longer influence and development, Fauvism in its own right became something of an important stepping stone for further developments in abstraction.

In terms of content, Fauvists simplified their forms but kept them fairly well recognizable. Fauvism was individualistic, intuitive, and often emotionally driven. Cubism, by contrast, took a more intellectual approach to the flat surface of a canvas, revealing form and space as something almost mathematical.

Fauvism works emphasized painterly qualities, characterized by rich colors and soft, figurative images whose felt impact often thrived on a lack of detail. Cubism, even in its earliest phase, was nothing if not analytical. Eschewing the academicism of its time, Cubist painters pushed abstraction to ever greater heights, relying less on representational likeness and introducing new relationships between color and shape.

The Spirit of Fauvism Lives on Today

Fauvism’s artists discovered a sense of freedom and the originality of its approach paved the way for contemporary avant garde art. Abstract Expressionists like Pollock might never have splashed and splattered paint so boldly if the Fauves hadn’t first shown that paint itself could be the star of the show.

However short-lived as a movement, Fauvism’s attitude proved infectious. Impressionism had already hinted that personal vision was more important than academic theories or elevated subject matter. Fauvism’s break from artistic conventions took Impressionism’s already radical departure to new extremes, challenging viewers to adopt new ways of looking at the world.

Fauvism-inspired wall prints bring wild, joyful colors into your home, reminding you daily that breaking the rules and trusting your instincts leads to the most authentic creative expression.